As a Sudanese diaspora Cairene artist, I was influenced by two distinct environments. At home, I lived the culture of Sudan. My mother would tell stories about her hometown in Old Dongla, Sudan on Fridays mornings over milky tea and ha’ysh (homemade Sudanese biscuits). She would remember her own childhood and how she used to dig with other children in search of “stone cats” (ancient Egyptian cat statues) to give to tourists in exchange for sweets.

I grew up captivated by my mother’s amazing stories of therianthropy (where humans take animal form), her family’s expeditions in the south to capture slaves, and how her father decided to leave the family slavery business and settle down on our island next to the river Nile.

The very smell of our house in Cairo evoked Sudan, with the scent of Bint el Sudan perfume mixing with incense. Memories of Sudan were also housed in a tin box of old family photos.

Family and friends visiting from Sudan would bring homemade peanut butter, spices, and cassette tapes from relatives back there. I first met my cousins during a trip to Sudan when I was six.

My father, a descendant of a Sufi family, came to Cairo in 1951 as a young scholar heading to Al Azhar University. He dropped out, bought a car, and worked as a taxi driver in the city he fell in love with. He only went back to Sudan once: for his wedding. His stories revolved around the Cairo of the 1950s and 1960s and his encounters with celebrities, including the time he met Mohamed Naguib, an Egyptian-Sudanese who became Egypt’s first president in 1953, and who found my father a job in an oil company.

My Egyptian school was another formative influence. It was there that I discovered a different version of the black identity that I lived in family stories and within the diaspora community. At school I studied a history in which the image of Sudan was negative, while the media constructed the infamous image of the ‘black’ Arab. It is this clash between different constructions of Blackness that I have had to endure and worked to understand.

Being raised in downtown Cairo, a cosmopolitan space and location of the American University, French schools, and many ethnic communities, opened my eyes to another layer of my black identity through encounters with diverse black communities. My outlook expanded further thanks to the American shows aired on Egyptian TV that presented an image of black characters different from the stereotypes found in Egyptian productions.

My practice as a painter has afforded me a space to recreate an identity where my Nubian heritage meets my Cairene present.

The 2011 revolution raised many questions about contemporary political and social history, and threw into question the imaginaire of the monarchy and foreign minorities created by sixty-years’ worth of post-1952 propaganda. Given these trends for constructive historical revisionism and contestation of negative images of the other, I turned to the British and Egyptian colonial archives in search of alternative images of Sudan.

I wanted to investigate the real history of slavery between Sudan and Egypt, especially how slaves became soldiers in the nineteenth century. In an attempt to allow silenced history to speak, I moved away from official historical sources, focusing my research on the “Egyptian” battalion (comprising mostly Sudanese) that fought during the second French intervention in Mexico in the 1860s. The Khedive had gifted those slave soldiers to Napoleon III. The result of my work is the no1: Black Ivory Project.

Starting with a list of names of Sudanese soldiers who fought in the Mexican French war, I came across an interview with a soldier, Ali Al-Jifoon Effendi, in an English magazine from 1902. He talked about his kidnapping as a child and how he fought as a soldier in three colonial armies, British, French, and Egyptian. Alongside the historical events that he recited, he told stories of transformation (therianthropy) that were similar to my mother’s stories. This spurred me to make an audio installation to tell his story. I decided to use his mother tongue, Shilluk, which is spoken by the southern Sudanese Shilluk tribe, a tribe linked to my own family’s history as slavers. First, I went to the Shilluk community school in Cairo, but I could not find a translator. Everyone refused to meet me because of my family’s past. Next I went to the priest of the Shilluk church to persuade him to nominate a translator. After an extended conversation, the priest agreed to translate and narrate the story himself.

During a residency in southern Morocco on one of the caravan routes to North Africa for slaves, I looked for slave culture’s influences on Moroccan culture and discovered that Sudan was not unusual as a family name and was referred to in slave songs (gnawa), with lyrics such as “Mother, they stole us from Sudan.” (Here Sudan refers to their unknown home in the wider region of Sudan, not the modern political borders.)

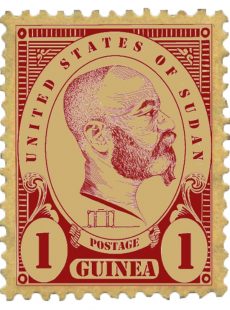

That experience led to the Alternative Museum of the Sudan, a project which investigates the identities of the Sudanese region (East Central, West, and Sub-Saharan Africa) as expressed in nineteenth- and twentieth-century colonial propaganda.

Modern colonial propaganda contributed to the formation of stereotypes of black communities and Blackness which we have internalized to become part of our vision of ourselves. With this understanding comes the possibility of reforming the image of Black identity from our own perspective. The exhibits of the Alternative Museum of Sudan display and articulate a hitherto unspoken history.

Amado Alfadni

C.V

Solo Exhibitions:

2018 Mahungu. SOMA art Gallery.Cario.Egypy.

2017 Ace of Spades ,SOMA art gallery, Cairo. Egypt.

2016 no1: Black ivory, Contemporary Image Collective (CIC), Cairo, Egypt.

2015 Typology, Ahmed Shawky museum, Cairo, Egypt.

2014 Black Holocaust Museum, Contemporary Image Collective (CIC), Cairo

2012 Leaving, Awan Gallery, Cairo,Egypt.

2012 The President,Gudraan gallery, Alexandria,Egypt.

2012 If I Were President, Artellewa Gallery,Cairo,Egypt2008-10mm, Artellewa, Cairo,Egypt.

2007 Africa 6 letters, Goethe Institute,Cairo, Egypt.

2007 The Color of the summer, New Cairo Atelier,Cairo.Egypt.

2003 Black and Yellow, Michelangelo Gallery, Cairo. Egypt.

2001 Why Not, Cairo Atelier,Cairo,Egypt.

Selected Group Exhibitions:

2021 Saturation, Cairo photo week, Egypt

2020 Amwaj virtual exhibition, Sulger Buel Gallery U.K

2019 After the Canal There was only “OUR” world, Ljubljana, Slovenia

Pop Art form North Africa, Madrid

2016 Storm, Künstlerforum, Bonn, Germany.

2014 Photophilia, Townhouse Gallery, Cairo. Egypt.

2013 UAMO Art Festival, Munich, Germany

2013 Super Market Art Fair, Stockholm, Sweden

2012 Passport Agency, Mattress Factory Museum- Pittsburgh, U.S.A

2011 No Glory, Form + Content Gallery, U.S.A.

2011 The Popular Show, Townhouse Gallery, Cairo. Egypt.

2011 Express Yourself, Darb1718,Cairo. Egypt.

2009 The Creativity of the Other, AinHelwan Culture Palace, Cairo.

2008 Annual Graffiti Festival, Mahmoud Mokhtar Gallery, Cairo Egypt.

2007 IntaFeen, Swiss Residency Studio, Cairo.

2006 Different Complete, Townhouse Gallery On-Site, Cairo Egypt.

2005 Small Pieces Salon, Portrait Gallery, Cairo.

2004 Ministry of Culture Youth Salon, Cairo Opera House Cairo.

2003 Day of Africa, Sawy Culture Wheel, Egypt.

2002 RatebSeddik Competition, Guest Artist, Cairo Atelier, Egypt.

2002 Small Pieces Salon, Palace of Arts, Egypt.

2000 Nissan Art Salon, Khartoum, Sudan.

Residencies

2017 Beyond Qafila Thania , Morocco.

2016-2017 Artist in residency Jiwar, Barcelona-Spain.

2016 Artist in residency Künstlerforum, Bonn- Germany.

2012 Artist resident at Mattress Factory Art Museum- Pittsburgh- U.S.A.

2012 Visiting Artist Carnegie Mellon University- U.S.A.

2011 Visiting Artist Hood University- U.S.A.

Curatorial projects:

2015 Detour. Vedionale (Bonn), Nabta Art center (Cairo). 2012-Arab Collaboration Project, Artellewa Space, Cairo.

2012 Kamala art salon “African artists in Cairo”, Nabta Art center,Cairo.